2020 has had a very rough start. Initially, I was not sure whether I should write anything about the new Coronavirus and the deadly disease it causes, Covid-19. After the virus went global and became a pandemic, every newspaper, magazine and talkshow has, understandably, incessantly talked about its fallout and how to deal with it. Living in a part of the world that is all too familiar with such virus outbreaks further adds to the attention it receives, even before the rest of the world was affected and rumours about a second SARS coming out of central China first emerged at the end of last year.

Amongst the barrage of news about the virus, an uneasy feeling has started to encroach me. It seems that the more we read and talk about the virus, the more we loose track of the origins of the trouble we have found ourselves in. Given the seriousness and scale of the virus’ onslaught I would have expected that, by now, the (global) discussion to focus more on the reasons that have contributed to the emergence of the deadly decease rather than on the development of its spread and resulting casualties. Of course, it is useful to be regularly informed about the health statistics, bottlenecks in supplies, economic damage, financial risks and (upcoming) travel restrictions. Indeed, you could say it is a sign of respect to be aware of the number of infections and deaths, and the exceptional effort of medical professionals around the world.

The question whether face masks are effective in public or not may be relevant in our current predicament, but it is hardly a meaningful one.

Yet would it not be worthwhile, and perhaps more effective, to shift some of the coverage to the actual causes of the virus outbreak? In addition to doing all we can to contain the outbreak and limit casualties, both policy makers and the public should deal more with questions on how to prevent certain outbreaks from happening in the first place. The search for potential answers is obviously a difficult one, which is why people tend to avoid such questions. The question whether face masks are effective in public or not may be relevant in our current predicament, but it is hardly a meaningful one. In essence, it addresses an issue that is at this moment of concern to many people but it does not help in explaining or preventing the issue itself.

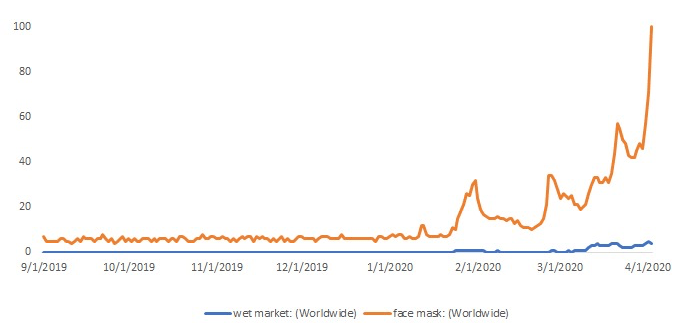

So can my uneasy feeling about the misfocused virus coverage be substantiated? To some extent, yes. A comparison of the key words ‘wet market’ and ‘face mask’ using Google Trends shows that the the former has received far less attention since the beginning of this year (see the graph below). This is obviously a very rudimentary analysis, but it does suggest that people’s attention is heavily skewed towards the consequences of the virus outbreak (such as wearing face masks) compared to potential causes of it (circumstances in Chinese wet markets).

To be fair, there has been quite some discussion around how the Coronavirus came about and whether China’s wet markets have played a significant role. One particular insightful piece published by news site Vox tries to explain why deceases such as the new Coronavirus tend to appear in China (see the video below). Whether you agree with this analysis or not, taking a closer look at one of the potential causes of the virus is certainly useful.

Unfortunately, such efforts have often been framed as a form of China-bashing or even outright racist. Intentionally referring to the ‘China virus’ or ‘Wuhan virus’, as president Donald Trump has repeatedly done, is clearly insulting and unproductive, but its underlying message in not completely without merit. Few would argue China as a country or the Chinese people are solely responsible for the outbreak of the virus. Counterarguments in the lines of racism are therefore misguided. Instead, an increasing body of research is merely suggesting that one specific part of the Chinese economy based on a certain tradition − namely the explosive growth of its wet markets and wildlife trade − is likely to play an important role in the creation of new viruses that can be harmful to humans.

Intentionally referring to the ‘China virus’ or ‘Wuhan virus’, as president Donald Trump has repeatedly done, is clearly insulting and unproductive, but its underlying message in not completely without merit.

Thus, the uptake of the reporting around wet markets is not to inflame people but rather to inform them. Personally, I’m quite convinced by the explanation that is put forward. As shown in the video, the industrialization of traditional wet markets and wildlife trade increases the chances of viruses transferring from one species to another, including humans. The commercial and political interests that prevent effective regulation further increases the problem. If we continue to look the other way and focus our attention only on the consequences of this virus − as illustrated by the search for information on face masks, for instance − then we should not be surprised when we find ourselves in a similar situation sooner than we think. After SARS and now Covid-19, let’s make sure Covid-29 does not become a reality.