It was hard to miss on the first of July this year: the Communist Party of China (CPC) celebrated its 100th birthday. A huge crowd of − staged or real, who knows? − Party enthusiasts celebrated on Tiananmen Square in Beijing while Xi Jinping, China’s president, summed up the Party’s achievements during a one-hour long speech. His message was clear: without the Party, China would not be where it is today. The centenary is a crucial milestone in the narrative that the CPC has promoted ever since it came to power in 1949. The Party’s actual story has been more mixed and, as we have seen in part one (The Pledge) and part two (The Turn), includes a number of unanticipated, dramatic twists. Our third and final act, The Prestige, captures the rise of Xi Jinping who over the course of the past decade has steered the country into an eerily familiar direction.

Before we turn to Xi Jinping’s road to power, it is important to understand the context in which Mr. Xi became General Secretary of the CPC in 2012 and president of China the year after. Since Deng Xiaoping introduced his ‘Reform and Opening Up’ campaign in the late 1970’s, China has gradually developed into a market-based, globalised economy. Hu Jintao, Xi’s predecessor, captured his somewhat liberal perspective into the so-called Scientific Outlook on Development. Apart from further economic development and liberalization, this concept emphasized the equal distribution of wealth, cultural diversity and human rights. (The latter included mostly economic and social rights, not its international version). Despite the continued crackdown on ethnic minorities in places like Tibet and prosecution of activists such as Ai Weiwei, many Chinese as well as Westerners were starting to believe China was becoming a more free and tolerant country. For many, the 2008 Olympic games in Beijing and the 2010 Shanghai Expo exemplified this belief.

The atmosphere of progress and freedom was palpable when I was living in Shanghai in the second half of 2012. The past decade under Hu’s leadership had brought ‘moderate prosperity’ for many ordinary Chinese without too much state interference. The city was experimenting with a free-trade zone aimed at attracting foreign investment and know-how. As a foreign student, my conversations with locals often revolved around what life was like in Europe. People were generally open-minded and spoke freely about the pros and cons of living in China. Even sensitive subjects such as the territorial row between China and Japan regarding the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands in the East China Sea could often be openly discussed. This mindset extended far beyond China’s most international city and could also be noticed while I was traveling through more remote areas.

The past decade under Hu’s leadership had brought ‘moderate prosperity’ for many ordinary Chinese without too much state interference.

However, the scene was about to change when Xi Jinping took the helm in November that year. Leadership shuffles in China are typically clouded in secrecy and, especially to the outside world, appear largely ceremonial. Yet few had predicted the radical shift in policy that accompanied Mr. Xi’s appointment as highest ranking official. At first, many commentators anticipated Mr. Xi to be a reformer who would continue the liberalizations put in motion by his predecessors. Even newspapers like The Economist were quite hopeful about China’s new leader. Mr. Xi started off with the largest anti-corruption campaign since the Mao era and, in doing so, quickly consolidated his power within the Party. Some argued that his enormous influence could in fact be used to push through difficult reforms. This turned out to be wishful thinking.

Instead, Xi reintroduced a political and economic orthodoxy reminiscent of the CPC’s early days. Critics and dissidents were silenced − which had started even before Mr. Xi officially came to power with the downfall of his main political rival Bo Xilai − and national economic champions were reigned in with red tape. This U-turn culminated in the removal of the presidential term limit in 2018, effectively granting Mr. Xi power for life.

With Xi in charge, the neo-Maoists were able to push for more traditional communist policies such as the dominance of state-owned enterprises and the central role of the Party in people’s everyday lives.

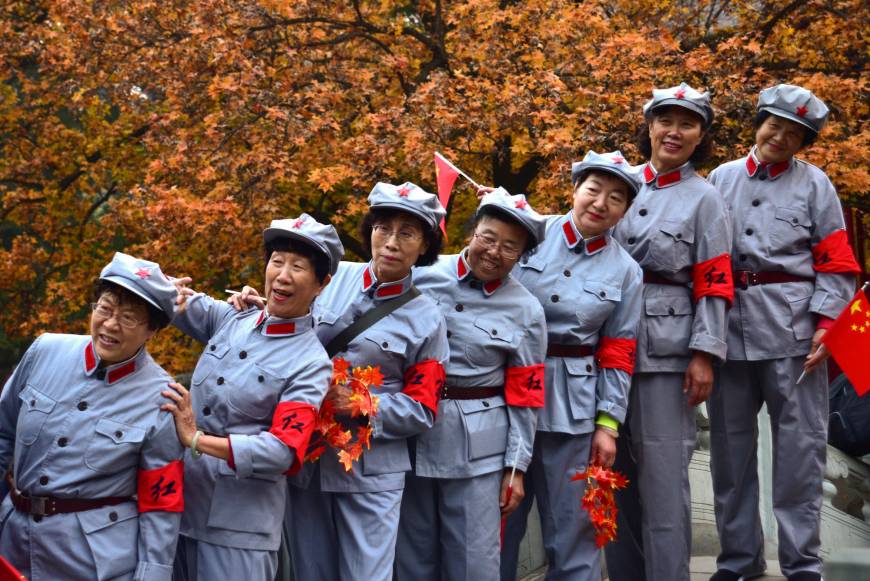

The return to a more authoritarian, ideological mode of governance has been linked with neo-Maoism, a political movement that emerged in the early 2000s and has enjoyed increasing influence since the first years of Mr. Xi’s rule. Jude Blanchette, author of the book China’s New Red Guards, explains the neo-Maoists are a steadfast supporter of Xi Jinping and view him as an ally in their quest to bring the country back to its communist roots. This group of individuals strongly disagreed with the road towards further economic liberalization under Hu Jintao. With Xi in charge, the neo-Maoists were able to push for more traditional communist policies such as the dominance of state-owned enterprises and the central role of the Party in people’s everyday lives. Often overlooked by foreign observers, Mr. Blanchette argues the neo-Maoists have helped shape the newfound ideological fervour of Mr. Xi and they continue to play an important role in Chinese politics.

Over the past century, the CPC has managed to evolve and remain firmly in power. Part one, The Pledge, explained how the Party was able to adapt the communist ideology in order to facilitate its victory in the civil war and reunite China under one banner. In the second part, The Turn, the Party embarked on a radical new course: the country opened up to the outside world and unleashed the spirit of capitalism. The third and final part, The Prestige, has shown how the CPC has recently revived its communist foundations and is turning inwards again. This analogy has hopefully enabled you to better understand the Party’s many twists and turns, and will help you make sense of the story that has yet to unfold.